Diabetic Retinopathy

Diabetic Retinopathy

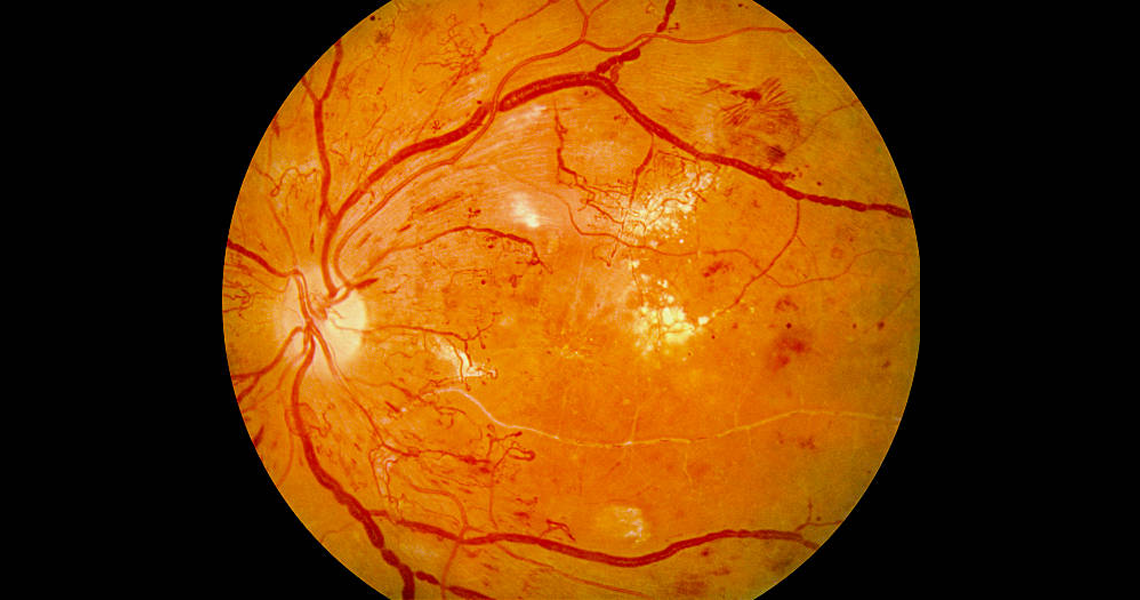

Diabetic retinopathy is a complication of diabetes that affects the small blood vessels in the retina — the light-sensitive tissue at the back of the eye. It is a leading cause of vision loss in people with diabetes, especially among working-age adults.

What Causes Diabetic Retinopathy?

High blood sugar over time can damage the blood vessels in the retina, causing them to leak, swell, or close off entirely. In more advanced stages, new abnormal blood vessels may grow (neovascularization), which can lead to bleeding, scarring and retinal detachment.

Types of Diabetic Retinopathy

Non-Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy (NPDR): Early stage with signs such as microaneurysms, retinal bleeding, and fluid leakage.

Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy (PDR): Advanced stage where new abnormal vessels grow on the retina, increasing the risk of bleeding and vision loss.

Diabetic Macular Edema (DME): Swelling in the macula (the part of the retina responsible for central vision) that can occur at any stage and significantly affect vision.

Treatment Options

Laser therapy to seal leaking vessels

Injections (anti-VEGF or steroids) to reduce swelling

Surgery (vitrectomy) for advanced bleeding or retinal detachment